Will Flanders

Noah Diekemper

It may be hard to believe, but Wisconsin is now commemorating its second anniversary of living with COVID-centric public policy. It was 2 years ago last Saturday that Governor Evers declared a public health emergency over the novel coronavirus, and our schedules and lives as we’d known them were upended. With Anthony Fauci warning that the pandemic is not over, and new variants springing up around the world, it seems like a good time to recap the past 2 years, and discuss where we go from here.

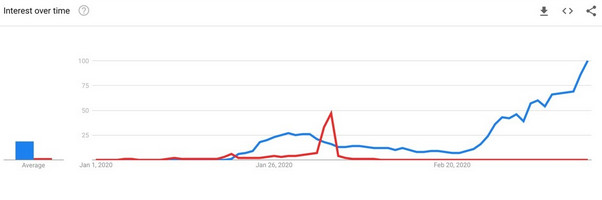

The following Google Trends graph (January 1 through March 10, 2020) shows that by the end of January public searching for “coronavirus” achieved about half the volume as “Superbowl” received. The graph depicts search frequency for “coronavirus” (blue) against “Superbowl” (in red) over time .

With the “trust the science” narrative that came to dominate mainstream media, it is perhaps surprising to remember that much of the earliest media coverage was focused on downplaying the threat posed by the virus. The subtler takes from the New York Times and the Washington Post cautioned that xenophobia, especially in the agency of the government, was a more dangerous threat. Some of them also opined that humans are bad at assessing the hard numbers of risks. For example, “Why worry more about [SARS, Ebola, Zika] than influenza, a far greater actual threat?” asked one Washington Post “Perspective” piece. That essay also warned about the human glitch that “when the news and our social media feeds are dominated by coronavirus, that danger becomes the biggest blip on our risk radar screen, pushing most other threats off, even if they pose far more peril.” Another Washington Post piece scolded America to “Get a Grippe . . . The flu is a much bigger threat than coronavirus, for now.” Finally, the least subtle Vox had the definitive (now-deleted) tweet on the subject: “Is this going to be a deadly pandemic? No.” They issued this on January 31, 2020, in spite of the fact that on January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization had declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Very rapidly, the media changed its tune as caseloads and deaths increased. So what did we learn through all this? Here, we review what we know of several key coronavirus policies.

Public Shutdowns

On May 18, Wisconsin became one of the first states to reopen for business when the state Supreme Court struck down the Evers administration’s Executive Order #28. COVID restrictions devolved to the local level at this point, and local government actions varied greatly in the extent to which they allowed normalcy. In a way, Wisconsin served as a natural experiment for the rest of the nation on whether shutdowns of public life were effective. If the state saw a huge spike in cases following reopening, this would serve as confirmation that shutdowns were the right approach. The table below, adapted from the Journal Sentinel, shows that this was not the case. Cases did increase over time, but not to any appreciable extent immediately following the Supreme Court decision.

Of course, if people did fully isolate themselves, simple logic dictates that the virus would decline. The transmission may indeed have declined—but between the virus’ long incubation period and reduced human interaction, the virus was never fully stopped. After all, almost everyone was still buying some new groceries if not having take-out delivered during this same time period, a possible transmission vector that seems to have been sidelined from public policy consideration because it was simply necessary.

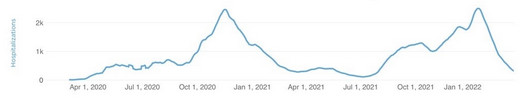

Whatever the case, the virus kept spreading, but the goal was achieved: hospitals were not overwhelmed with people dying en masse of coronavirus whilst also clogging care facilities that could have been addressing treatable sicknesses and injuries at the same time.

But the public policy emergencies measures kept coming.

Masking

Masks became among the most visible and controversial aspects of the pandemic. Even as mandates have dropped around the nation, mask-wearing has become normalized, or even expected, in some areas of the country. The effects of masks in the state are difficult to untangle, as some of the areas that kept mask mandates in place also had some of the most restrictions in general for social distancing.

Research around the world yielded mixed results: some studies have found a small, positive effect of masking in reducing the spread of the virus, while others have found no effect. Particularly when it comes to cloth face masks, growing evidence suggests they serve as little more than a virtual signal. And by giving people a false sense of security about their safety from the virus, and (in some cases) causing people’s hands to be nearer their faces more often, there is a distinct possibility that mask wearing could have incentivized worse behavior and contributed to the spread.

Harm to Education

By the fall of 2020, many events and businesses were allowing the public back in, at least in a limited capacity. Yet despite evidence of extremely limited risks to children, many school districts dragged their feet on reopening. WILL published a study finding that the presence of a teachers union and the politics of a particular region, not necessarily the local presence of the COVID-19 virus, appears to have driven district-level decisions to start the school year with in-person learning. More recently, a WILL study estimated that districts that shut down had far greater proficiency declines than those that remained open—a problem that educators will have to deal with for years to come.

Vaccines

While controversies have arisen about vaccine mandates, there is little doubt vaccines themselves have proven effective at reducing the risk of coronavirus. In December 2021, Wisconsin DHS released data comparing cases and deaths among the vaccinated and unvaccinated population. In a hypothetical population of 100,000 vaccinated individuals, 18 hospitalizations and 3.6 deaths would be predicted. In that same population of unvaccinated individuals, 176 hospitalizations and 50.8 deaths would be predicted. There are concerns about how long the vaccine lasts, and the length of effectiveness among children. However, it is clear that vaccination remains the best pathway to avoiding coronavirus.

Two Years to Flatten the Curve

There is little doubt that some will be unwilling to let go of the pandemic narrative. So, what lessons are we to take away from this, to avoid repeating mistakes in the future?

One of the best lessons, ironically, might be something that we knew all along: in the words of that January 31, 2020, Washington Post piece, some risks feel scarier than others because of “what Roger Kasperson and colleagues call the “social amplification of risk.” We only have so much cognitive bandwidth, and as social animals, we have evolved to pay closer attention to whatever a lot of other people are already paying attention to.”

Or consider the following storytelling from America’s most circulated newspaper, The New York Times: “At a recent high school sports event in my community, I ran into a teenager whom I have known for years. We gave each other enthusiastic hellos and started to have a conversation. But it was impossible. There was some background noise in the gym, and he has a disability that affects how he communicates. Usually, it does not keep us from talking at length. This time — with both of us masked — neither of us could follow what the other was saying. We smiled and gave up. It was not a big deal, but it reminded me that masks have both benefits and costs [emphasis added].”

That was published February 8, 2022. Every ordinary person dealing with masks knew all about those risks, had been intimately familiar with them, for nearly two years by that point. But apparently even this modest acknowledgement that costs exist to that decision needed to be artfully couched, and could then be presented as news.

Most average people dealing with masks knew all about the risks, had been intimately familiar with them, for nearly two years by that point. But apparently even this modest acknowledgement that costs exist to that decision needed to be artfully couched, and could then be presented as news. This is the biggest lesson for policymakers looking back: we ought to be far more measured in our response to future crises. Specifically, rather than only considering the negative consequences of one specific emergency, concerns about education, the economy, and mental health ought to be considered before overarching public policy decisions are made to the health department.