By: Libby Sobic and Will Flanders

After the “year of school choice,” it is important not to get complacent as attacks on school choice and autonomy from traditional districts continue. And National School Choice Week is a good time to consider what obstacles stand in the way of parent choice. An attempt to unionize teachers at the largest charter school system in Wisconsin could be the latest canary in the coal mine.

Earlier this month, teachers at Carmen Schools in Milwaukee announced that they will attempt to unionize. This is part of a national trend. Recently, a large charter network in Pennsylvania voted to unionize. In Chicago, about one quarter of charters are now unionized, and even went on strike in 2020. To the outside of observer, this may seem somewhat innocuous. But, in many ways, unionization attacks the very heart of what charter schools were designed to be.

First broadly implemented in Minnesota in the early 1990s, charter schools were created to provide a public-school alternative to traditional public education. They were meant to empower passionate teachers and administrators who saw a different path forward from the status quo. These educators could then set up contracts (or charters) with the school district to implement their vision. Independence and diversity from the local school district are key to the success of charters, but unionization can pose a threat to that.

Wisconsin provides a perfect venue for highlighting this: Along with charter schools like Carmen, the state has other charter schools that are much more heavily tied to the local school district, including in the area of unionization. A 2017 study I (Flanders) authored, showed that this second type of charter did not have a performance advantage on state tests despite spending far more per student than independent charters. Indeed, unionization in general is associated with slightly lower proficiency and graduation rates across the nation according to recent research.

We’ve referred to this second type of charter school as a “charter in name only.” The reasons for this are myriad, but center on the notion that working in a charter school requires a higher level of “buy-in” from teachers than may be required in a traditional school. Rather than adversaries, teachers and administrators have to be on the same page in order to implement the school’s unique vision. In a unionized school, this spirit of cooperation towards a common goal breaks down.

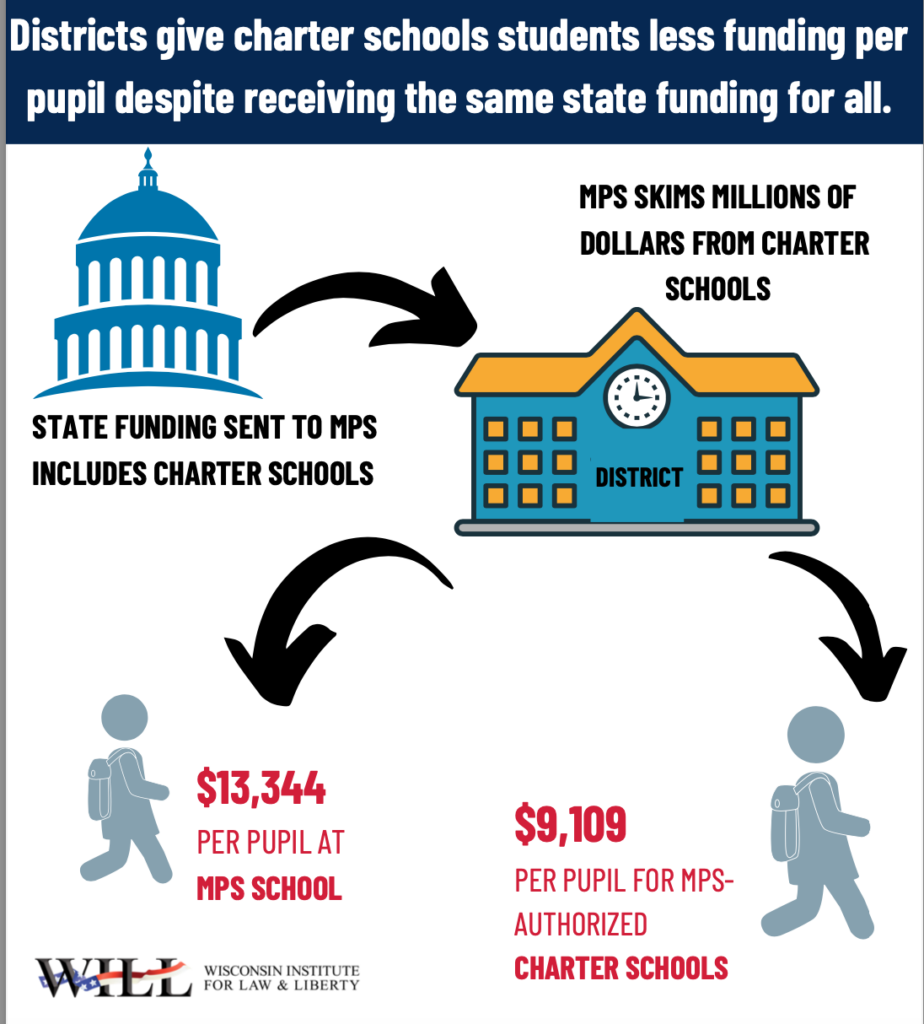

There is no doubt that working in a charter school presents unique challenges for teachers. Among the demands of Carmen’s teachers are higher pay and a work week that is capped at 40 hours. But if charter school teachers are after more pay, they would generally be better served by complaining to their state legislature than their school leadership. A 2020 analysis found that charter schools around the country receive $7,796 per student less in federal, state, and local funding than traditional public schools in the same area. In Milwaukee, where the Carmen schools are located, these schools receive $9,109 per student which is $4,000 lower than its authorizer, Milwaukee Public Schools. Despite the gaps in per-pupil funding set by the district, Carmen schools have grown to be the largest charter network in Wisconsin and serve over 2100 students across Milwaukee.

Charter schools today face challenges from all sides. For many on the left, they have been lumped together with private school choice as unwelcome competition for the public-school monopoly. While former President Barack Obama was a supporter of charter schools, his former Vice President Joe Biden came into office as president fighting to reduce their funding. Coupled with the move towards unionization, the extent to which these schools can serve their original vision is an ongoing question. It is important that legislators recognize the important role that charters can serve as a public-school alternative to traditional education, and work to protect that independence.

Sobic is director and legal counsel for education policy and Flanders is the research director at the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty.