Along with casting votes for President and US Senator, Wisconsin voters across the state will have school referenda to consider. These referenda ask voters’ permission to issue debt for something specific or to exceed the annual revenue limits set by state law, in either case by increasing voters’ property taxes. Voters typically hear from their school districts about what the expenses are needed for, but specific information about what that would

mean to their taxes might be buried, or not explained at all. To help alleviate that, WILL has created the referendum cost calculator above.

This calculator provides an estimate of what new school spending could do to property taxes in your area. It includes estimates for 111 of the 121 school districts that are voting on referenda this November 5. For the remaining 10, the relevant information could not be found online and was not provided in response to open records requests. This calculator (and the underlying data) does have some important limitations and caveats, discussed throughout and enumerated at the end of this post.

Takeaways from Calculator

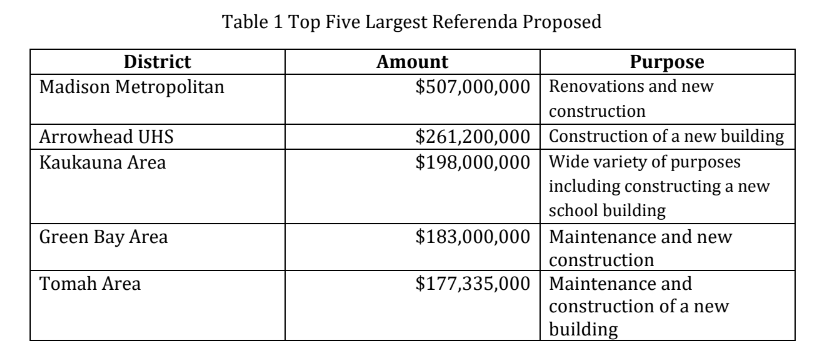

This November, school district referenda are putting a grand total of $4,284,530,513.00 on the ballot. The top five most expensive referenda that are being voted on, which account for nearly a third of the total money at stake, are highlighted in Table 1. By far the largest single referendum is in Madison, with taxpayers being asked to increase their taxes by $500 million—that amounts to more than 10% of the total money being asked for

statewide. Perhaps the most staggering proposition, though, is the Arrowhead School District’s. Arrowhead is a high school-only district with just 2,038 students according to the most recent DPI data. This proposed debt would amount to about $128,164 per student.

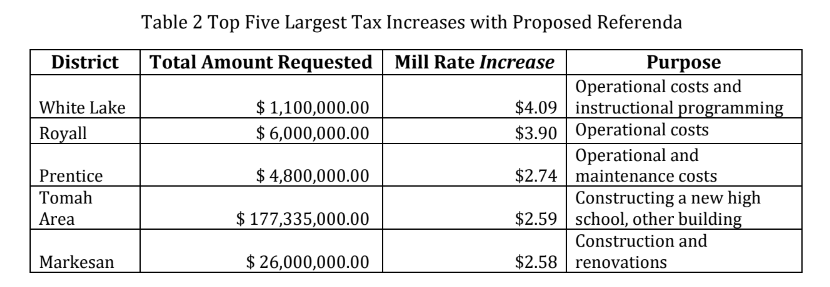

Of course, absolute costs are different from tax increases. We also look at the 5 biggest proposed property tax increases, computed as the difference between the tax rate that would result if the referendum passes versus the tax rate if it does not pass. This property tax is typically expressed as a “mill rate.” (A mill rate is the amount of money per $1,000 of property value that is taxed for school district purposes each year.) The top five largest property tax increases are highlighted in the table below. Tomah Area is the only one to appear on both top 5 lists, thanks to its proposal to acquire land and build a new high school campus on it, in addition to converting existing buildings (the current high school will be turned into a middle school, etc.). Note that computing these increases is subject to the same data limitation described below, i.e., where a school district does not have a specific mill rate planned for if their referendum fails, we use the current mill rate.

Frivolous Spending?

At least eight of the referenda include the word “athletic,” suggesting a purpose of the referendum is something beyond the core academic functions of the school district. Unsurprisingly, this figures into the referendum in Arrowhead, whose ballot proposition mentions “construction of a new high school building, including an auditorium and pool” and “athletic facility and site improvements.” Others are described in such an ambiguous way that it’s difficult to gain any understanding of what the district plans to do with the money. For example, the description of a referendum in Ithaca is as follows:

“Resolution providing for a referendum election on the question of the approval of a resolution authorizing the school district budget to exceed revenue limit by $1,300,000 per year for four years for non-recurring purposes.” What those “purposes” are is apparently left completely to the imagination of district leadership.

2024 Referenda in Context

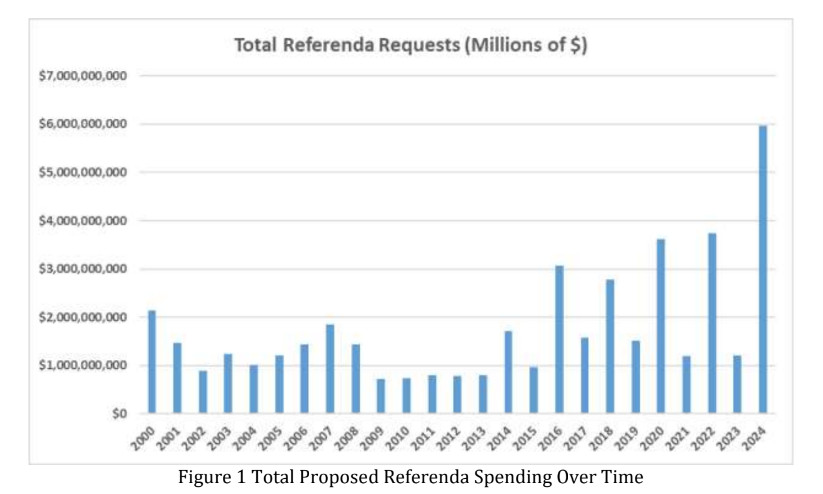

Figure 1 depicts the amount of money requested by school districts in referenda every year since 2000. The numbers are all inflation-adjusted to current-day levels. 2024 is by far the highest bar on this chart, with nearly $6 billion in new referenda spending proposed between the Spring and Fall election cycles. This dwarfs the second highest year—2022—by more than $2.2 billion.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of referenda in each year since 2000 that were conducted in each month. Over time, we can see a trend away from the “other” months, as well as away from holding referenda in February. April and November referenda have increased. The spikes for April come in off-years, some of which have no fall elections.

The percentage of November referenda this year has spiked beyond most previous years. This applies to the number of referenda being considered as well. The 139 referenda around the state represent the highest number on this chart going back to the year 2000.

Transparency

As mentioned, this calculator includes estimates for 111 of the 121 school districts that are voting on referenda this fall. The remaining 10 did not have the relevant information posted online anywhere that we could find and also have not provided that information clearly through open records requests. Six in particular did not post the information online and provided no response or acknowledgment to open record requests (initially made

between July 24 and September 3, depending on when it was known that districts would have a referendum): Bonduel, Darlington, Juda, Oakfield, Viroqua, and Washington Island. The other 4 have either offered a records request acknowledgment or have provided some materials, just not the relevant information for this tool. In the past, WILL has proposed that additional transparency measures be put in place by the legislature to ensure taxpayers know what they are voting on. The lack of responses from some districts here highlights the importance of that once again.

Conclusion

School districts continue to rationalize the need for so many referenda with the claim that spending has not kept up with inflation. But this is only true if you look at spending in 2009 to 2011 as the baseline. Those years brought a massive infusion of federal money following the Great Recession. The reality is that we are spending more than at any other point in our state’s history according to data from the Department of Education. Voters have the right to raise their education spending through the referendum process. But they also ought to ask: when is enough enough?

Calculator Limitations

Although we strive to provide a simple question with a simple answer, there are important caveats due to limitations on data and to some variety amongst this November’s referenda.

Referenda can begin impacting property taxes in different years. Issue-debt referenda are presumed to begin impacting property taxes in the next (i.e. 2024-2025) school year; operational referenda can specify in the ballot language which year they begin taking effect, although some remain silent on that point. If the language of the ballot does not specify and if we could not otherwise ascertain it, we assume it to be the 2024-2025 school year.

We note which school year we consider a referendum to begin taking effect in. The full descriptions are included and visible for each district, except for Wauwatosa’s two descriptions which were so much longer (a grand total of 1,830 words) than all others that we use their “Brief Descriptions.”

About 17 districts are voting on two different referenda this November. We only calculate the outcomes where either both pass or both fail.

Note that some school district’s operational referenda specify exceeding the revenue limit by different amounts from one year to the next. For instance, Madison Metropolitan School District proposes to exceed the limit by $30 million for two school years and by $20 million for every school year thereafter; on the other hand, the Niagara School District specifies amounts that increase from one year to the next. We only present the projected impact for the first year impacted. The full descriptions are included to make it easy to see whether a district is specifying this.

In cases where school districts provided a future projected mill rate for the scenario where the referendum does not pass, those are used. If not, we present the taxes implied by either the current mill rate or, if the referendum is going to begin in the 2025-2026 school year or later, the mill rates projected for the school year immediately preceding. Some (like Platteville) have considered multiple options but, to our knowledge and as of this writing, have not made a decision yet.

One complication in computing the expected impact is that some school districts (like Platteville) have been exceeding the limit already in order to pay off existing debt (as is allowed under state law). This “Fund 39” money is projected to decrease moving forward, which is why some school districts have the prospect of lower taxes if a referendum to exceed the revenue limit passes.

A similar difficulty is in school districts that previously passed an operational referendum that is expiring and are now proposing another operational referendum to replace it in the same amount (Janesville, for example). These districts have often not computed what a mill rate would be absent this extra funding, and we have no educated estimate, so the published impact is $0 even though the reality is almost certainly that property taxes would decrease to some amount if the referendum is voted down.

We assume no changes in the assessed value of homes, which may underestimate the change in property taxes that actually materializes. If you have your own estimate for how your home’s assessed value may change in the next year, you can enter that value with the slider and see what the impact would be. We have seen different school districts anticipate anywhere from 2% (Cameron) to 7% (McFarland) increases in assessed value; these adjustments are usually compounded annually.

Some school districts are voting on referenda but did not respond to open records requests and did not have materials publicly posted that we could locate that were needed to make these calculations.