By: Will Flanders

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government shelled out $189.5 billion to school districts across the country via Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding. Wisconsin was no exception. Across three rounds of ESSER funding, the state and school districts received more than $2.4 billion dollars. Despite federal requirements that ESSER money be used to supplement rather than replace existing spending, many school districts are clamoring to keep programs in place that were largely funded with ESSER money. Indeed, DPI has said that they will “be advocating to increase funding for schools to make up for the loss in ESSER funds.” The end of ESSER funds is also being blamed for a record number of school districts going to referendum this Fall.

But a critical question remains: Is there evidence that ESSER funding achieved its intended goal of addressing learning loss? With the deadline for spending ESSER dollars approaching at the end of September, now is an opportune time to assess whether the funding effectively mitigated and reversed the educational setbacks caused by the pandemic. Combining data from the state report card with data on district funding allocations from the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, we find that only one area of spending bears a strong relationship to learning loss improvement.

Analysis

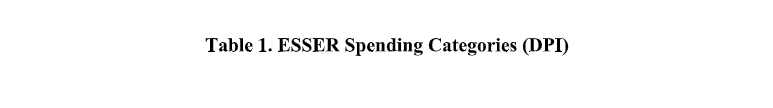

The Edunomics Lab provides ESSER spending data in a number of categories. These include spending on mental health services, afterschool and summer school programs, and technology among others. While most allocation categories are the same across all three rounds of ESSER, funding for continuing staff employment was only available in ESSER I.

Table 1 below provides one example from DPI’s guidance documents of an expense that fits in each category. Many more can be found in that document.

As a measure of whether ESSER funding had an impact on student achievement, we compare proficiency rates on the Forward Exam from 2018-19—the last school year before the pandemic—with rates from 2022-23—the most recent school year with data recorded on the same scale. To account for other reasons that proficiency may have changed at a different rate, we include control variables for the demographic makeup of the school and disability rates. The key independent variables are the percentage of ESSER funding that went into each category across all three rounds of ESSER.

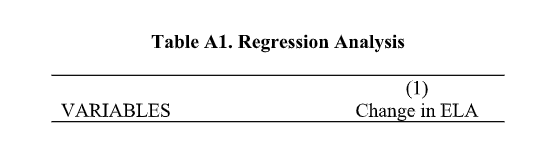

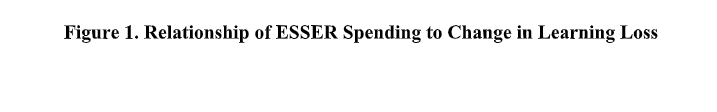

We analyze this data using a regression analysis with the change in ELA proficiency as the dependent variable. The results of this regression analysis are reported at the end of the blog post. Figure 1 visually depicts the areas of spending that were shown to have a meaningful relationship to improved outcomes in the model. Bars above the line mean that the variable had a positive effect on helping students rebound from school closures. A bar at the 2% mark would mean that districts that invested in this area saw proficiency rebound 2% more than districts that spent in other areas.

First, I included one control variable to the right of the red line for discussion. This is the percent low-income in the school district. This highlights, once again, that students from low-income families suffered the most learning loss during the pandemic. This effect can be interpreted as follows: a hypothetical school district with 100% low-income students would be expected to have experienced an 8% larger drop in proficiency than a hypothetical district with 0% low-income kids independent of other factors like ESSER spending.

The ESSER spending factor with the largest demonstrable relationship to reducing learning loss was spending on technology. A district that spent all of it’s ESSER funding on tech would be expected to have experienced 7.19% less learning loss by the 2021-22 school year. This makes some sense—access to technology was one of the biggest impediments to learning during the pandemic. School districts that eased that process appear to have achieved better outcomes.

Other factors that had some relationship to improving learning loss were long-term closure spending and preparedness spending. However, the asterisk on these two factors means that they were only significant at the p<.1 level. For social science research, this is a debatable level of significance that researchers are weary to make a big deal over. So of $2.4 billion spent by the federal government, only one category of spending appears to have been effective at fighting learning loss, three had no discernible effect, and two had a marginal effect.

Why Are the Effects So Limited?

One might question how an infusion of more than $2 billion into K-12 education could have such little impact on improving student outcomes. One of the key reasons is that much of what fits into the “other” category wasn’t related to addressing learning loss at all. DPI guidance for ESSER III notes that only 20% of money received must go towards learning loss recovery.

The Journal Sentinel provide examples of some districts utilized their funding in a recent article. Milwaukee Public Schools, for instance, used ESSER III money to upgrade it’s athletic facilities, while Wauwatosa used the funding to purchase student furniture and a “building and grounds work truck.” According to WPR, Wisconsin Rapids used to hire staff from Boys and Girls club to provide pre-school day care at schools. Racine Unified used funding to hire two “family engagement liaisons.” Some of these uses of funding may not be horrendous on their own, but one questions whether ESSER funds should have been used in these ways given that the state has still not recovered fully from pandemic-era learning loss.

Conclusion

While the ESSER spending numbers are not finalized and will need to be updated once all the spending data is completed, the preliminary evidence suggests that DPI’s effort to continue ESSER-level spending is misguided. Whatever technology needs existed for school districts have likely already been met, and no other category of spending shows strong enough evidence to warrant asking more from state taxpayers.